Delegation of Authority: Striking the Right Balance Between Governance and Management

This month’s column revisits a reoccurring conversation regarding a port commission’s delegation of authority resolution. Several newly elected commissioners recently began their terms, and many ports are in the process of reviewing, updating, and reauthorizing their delegation of powers resolutions (as was recommended in last month’s column). I thought it would be helpful to discuss this tool and the various manners in which ports utilize it.

Port powers are broad, and as a result, offer ports across the state the flexibility to implement projects and programs which cater to the needs and opportunities of your communities. This is a good thing. Port powers are primarily provided for in Chapter 53.08 RCW, but also exist more broadly in the other chapters of the port’s statute and elsewhere in Washington laws.

This column addresses (1) why a commission should delegate, (2) what a delegation of authority is comprised of—including its legal authority, and (3) how to implement and managethe delegation effectively within your port.

1. Why Delegate?

The short answer to this question is efficiency. Given the volume of work performed by the port and the limited available time of the commission, having a well-crafted delegation of authority in place allows the commission to avoid the minutia and focus on the big strategic decisions for the port. The broad powers of the port are vested in the commissioners acting together as the port commission. The commission can only exercise its powers in an open public meeting because the Open Public Meetings Act (“OPMA”) requires that any action of the commission be deliberated and carried out openly to the public. 1 Some consequences of not having a delegation, and thus, requiring all the decisions of the port to flow only through the commission include:

- Inability to respond quickly to constituent, customer, or tenant needs

- Creates a bottleneck of decisions and a loss of efficiency in port operations while decisions are left unaddressed or on hold between commission meetings

- If a decision is needed immediately, it creates extra administrative work to call a special meeting

- Bogs down commission meetings with management and operational decisions, diverting valuable time away from the commissioners’ consideration of the big-picture, strategic decisions that will govern the future of the port

- Underutilizes professional port staff who could be effectively handling management and operational matters given their years of experience, knowledge, and relationships within the industry

A port that requires every decision, or even the majority of decisions, to run through their commission likely will limit what that port can accomplish as compared to a port that implements an effective delegation of authority and strikes the right balance between governance decisions (for the commission) and operational/management decisions (for the executive director or managing official (“ED/Manager”)).

2. What is the Delegation of Authority?

The delegation of authority is a written resolution passed by the commission that assigns certain powers of the commission to the port’s ED/Manager. The statute that allows the commission to delegate is RCW 53.12.270, which provides:

(1) The commission may delegate to the managing official of a port district such administerial powers and duties of the commission as it may deem proper for the efficient and proper management of port district operations. Any such delegation shall be authorized by appropriate resolution of the commission, which resolution must also establish guidelines and procedures for the managing official to follow.

(2) The commission shall establish, by resolution, policies to comply with RCW 39.04.280 that set forth the conditions by which competitive bidding requirements for public works contracts may be waived.

Other than subsection (2) which requires the delegation to include policies to comply with public works competitive bidding requirements, and a few other powers reserved to the commission by other statutory provisions noted below, a commission has a great deal of flexibility in what it can include in its delegation of authority.

Typical provisions that are in a delegation of authority include:

- Express authority to make certain decisions based on budget line items or as a percentage of the budget

- Management of staff—hiring, firing and reorganizing (including wages and benefits within the budget)

- In cooperation with the port’s legal counsel, management of litigation, including settlement of claims for, and against, the port up to a certain dollar value

- Public work change orders (within the budget)

- Contract review and approval for consultants (within the budget)

- Leasing and licensing of port property

- Purchasing equipment and supplies (within the budget)

- Sale of surplus property per RCW 53.09.090

- Authority for write-offs up to a certain dollar value

As may be obvious based on the above examples, a critical tool that should accompany and inform the delegation of authority is the budget passed by the commission. The best practice is for the delegation of authority to be tied to the budget. This budget-based management allows the commission to provide the framework for the decisions within the delegation resolution, along with financial limitations set by then commission in the budget, to properly guide the ED/Manager’s decisions.

The commission is ultimately responsible for the port. Too little delegation results in a commission that is bogged down, but too much delegation may create an environment where the commission loses touch with important operations at the port. Striking the correct balance is key. The general framework for striking this balance, employed by many ports across the state, is that governance decisions and big-picture planning are done by the commission, while management and operational decisions are made by the ED/Manager. This varies from port to port.

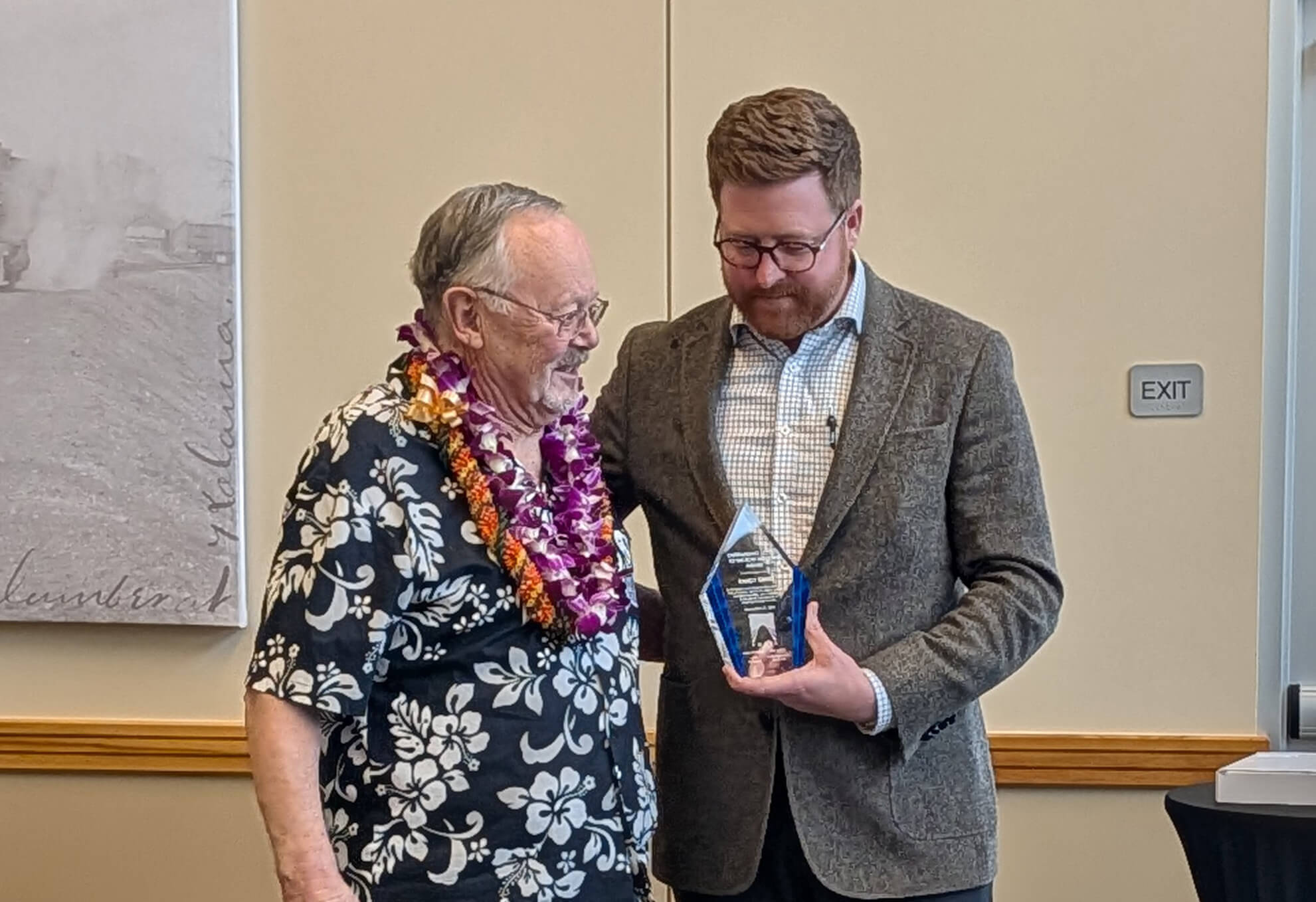

The delegation reflects the trust and confidence the commission has in its ED/Manager. Often times, commissions have narrower powers for a new ED/Manager because they are just beginning to build that trust. Whereas, an ED/Manager that has been with a port for many years may have more authority because the commission and the ED/Manager have a longstanding working partnership.

There are certain tasks statutes that cannot be delegated and must remain a decision of the

commission. These decisions include:

- Adoption of the Comprehensive Scheme of Harbor Improvements in RCW 53.20.010

- Adoption of, or amendment to, the budget

- Sale of property in excess of the amount identified in RCW 53.08.090(2)—currently $23,340

- Adopting personal service contracting policies per RCW 53.19.090

- Setting commissioner compensation

- Revising commission districts

- Creating industrial development districts per Chapter 53.25 RCW

- Establishing a tax levy

Determining which duties are “non-delegable” can be complicated, but your port attorney can help with this analysis.

3. How to Implement and Manage a Delegation of Authority?

Hopefully your port already has a delegation of authority. If not, consider reaching out to other ports around the state to get a sample of what they use as a starting point and work with your port staff and legal counsel to craft an appropriate delegation of authority for your port. Even if you already have a delegation of authority, it is a best practice to review and update that delegation annually. Changes or updates should be aimed at right sizing the delegation to your port’s needs and striking the appropriate governance versus management/operational balance between the commission and the ED/Manager. You should avoid concepts in a delegation that are a part of an employment agreement with the ED/Manager.

The delegation should be undertaken to make the port more efficient or to provide more time for the commission to govern. The delegation of authority is a tool—not a hard and fast rule. Simply put, just because the delegation authorizes an ED/Manager to make certain decisions without commission approval, doesn’t mean that the ED/Manager needs to make that decision. If there is a decision that is within the delegation, but nevertheless relates to a significant or strategic matter that the commission is handling, it would be wise of the ED/Manager to take that decision to the commission. When in doubt, take it to the commission.

Even when decisions are clearly within the delegation of authority, it is advisable for the ED/Manager to create a notification loop with the commission concerning significant use of the delegation of powers. This loop could be part of the director’s report at a commission meeting, in one-on-one meetings between the director and the commissioners, or a combination of these methods of communication. Good communication is the key. Again, the effectiveness of the delegation is an indication of trust between the commission and the ED/Manager —regular and effective communication is critical to building that trust.

As always, if this issue is of particular concern at your port, work with your port’s legal counsel to address your specific questions and, if appropriate, to draft a resolution for commission approval of the expenditure.

If you have a question for Knowing the Waters, please e-mail me at tschermetzler@csdlaw.com

1 RCW 42.30.010 and .060.